- Home

- Hua Laura Wu

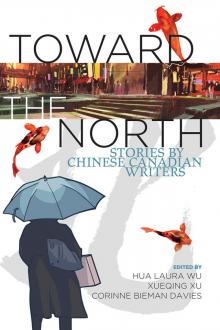

Toward the North

Toward the North Read online

TOWARD THE NORTH

Copyright © 2018 Hua Laura Wu, Xueqinq Xu, Corinne Bieman Davies

Except for the use of short passages for review purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced, in part or in whole, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically, including photocopying, recording, or any information or storage retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Collective Agency (Access Copyright).

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada.

Cover design: Val Fullard

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Toward the North : stories by Chinese Canadian authors / Hua Laura Wu, Xueqing Xu, and Corinne Bieman Davis, editors.

(Inanna poetry & fiction series)

Some stories translated from the Chinese.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77133-565-2 (softcover).-- ISBN 978-1-77133-566-9 (epub).--

ISBN 978-1-77133-567-6 (Kindle).-- ISBN 978-1-77133-568-3 (pdf)

1. Chinese Canadians—Fiction. 2. Immigrants—Canada—Fiction. 3. Chinese—Canada—Fiction. 4. Canada—Emigration and immigration—Fiction. 5. Canadian prose literature (English)—Chinese Canadian authors. 6. Canadian prose literature (English)—21st century. 7. Short stories, Canadian (English). I. Wu, Hua Laura, 1952–, editor II. Xu, Xueqing, 1957–, editor III. Davies, Cory Bieman, 1948–, editor IV. Series: Inanna poetry and fiction series

PS8323.C5T69 2018 C813’.01088951 C2018-904378-4

C2018-904379-2

Printed and bound in Canada

Inanna Publications and Education Inc.

210 Founders College, York University

4700 Keele Street, Toronto, Ontario M3J 1P3 Canada

Telephone: (416) 736-5356 Fax (416) 736-5765

Email: [email protected] Website: www.inanna.ca

TOWARD THE NORTH

STORIES BY CHINESE CANADIAN WRITERS

edited by

Hua Laura Wu

Xueqing Xu

Corinne Bieman Davies

INANNA PUBLICATIONS AND EDUCATION INC.

TORONTO, CANADA

To new Canadians

and those who support them.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Hua Laura Wu, Xueqing Xu,

Corinne Bieman Davies

Jia Na Da/Canada

Yuanzhi

Grown Up

Xi Yu

The Abandoned Cat

Ling Zhang

West Nile Virus

He Chen

Hana No Maru

Shiheng

Vase

Yafang

The Smell

Xiaowen Zeng

Little Weeping Millie

Daisy Chang

Surrogate Father

Bo Sun

An Elegant but Stiff Neck

Tao Yang

The Kilt and Clover

Xiaowen Zeng

Toward the North

Ling Zhang

Contributor Notes

Acknowledgements

Introduction

HUA LAURA WU, XUEQING XU, CORINNE BIEMAN DAVIES

Originally written in Chinese, these twelve stories have been translated into English to make them available to a general audience, and to scholars and students in Canada and abroad.These are stories of immigrants by immigrants. They reflect how new immigrants struggle to integrate into a new Canadian world; how they cope with gender and class issues, racial bias, cultural differences, and unfamiliar social norms. All the works have been published in Chinese literary magazines in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, or in literary columns of Chinese newspapers in North America. Some of the writers have received major literary awards in China; a number of their works have been adapted into movies and TV series in mainland China. The stories included in this anthology were written in Canada between approximately 1990 and 2010. The titles of the original journals in which the stories first appeared have been translated into English.

Toward the North is the first volume of its kind published in Canada. The story writers in this volume approach life quite differently from the second or third generation Chinese-Canadian authors writing in English (who are familiar to us), with their much vaguer sense of distant cultural roots. Having grown up and been educated in China, the new immigrant writers introduced here (in translation) retain strong cultural bonds with their homeland. Their stories about Chinese transplantation into Canadian society are tinged with deep cultural sentiment, fresh feelings of Chinese transnational and cross-cultural experience, and a strong sense of ethnic predicament. The fiction of second or third generation Chinese Canadians tends to be filtered through the focus of the children or the grandchildren of Chinese immigrants.

The title story “Toward the North” by Ling Zhang recounts Zhongyue’s one-year teaching experience on a reserve near Sioux Lookout, Northwestern Ontario, as a specialist in child psychology. His pedagogical practice leads him to befriend a Métis boy and his mother; he becomes a witness to tragedy resulting from cultural clashes. It presents its theme of cultural and personal liberation in a famous and remembered song from the time of The Cultural Revolution:

Go toward the north, go toward the north

The children in the south are looking for their liberators.

All of the authors, but one, in this collection lived through The Cultural Revolution in China from 1966 to 1976. The context of this song and the time period lead to further layers of meaning in all of the stories.

Enter, then, into the worlds of wives, lovers, husbands, children, and babies, grandmothers, liars, murderers, immigration scams, vases, cats, and ultimately liberation.

This anthology meets the increasing demand for fiction by Chinese-Canadian writers for study in colleges and universities. More significantly, perhaps, it will entertain general readers, and encourage understanding of contemporary Chinese Canadian life in our multicultural land.

Jia Na Da/Canada

YUANZHI

FENG JIAN STUMBLED OUT of the hospital in a daze. Heading towards the parking lot, he rummaged for the car key in his pocket. Perhaps he had left it in the delivery room. Or he might have left it in his wife’s hospital room. He was just about to turn back when he realized the key was in his other hand. He had been holding it so tight that his palm was damp. “Son of a bitch!” He spat out the curse as he opened the car door and quickly got in. He inserted the key into the ignition, turned it to the right, and the engine purred into action. He released the brake, put the shift in drive, and was just about to step on the gas when he realized that he had forgotten all about the seatbelt. So he shifted back into park, fastened the seatbelt, and started all over again. Finally, he drove out of the parking lot, slowly and unsteadily.

When he merged into the westbound traffic on Finch Street, the sun was setting. Driving into the red glare, Feng Jian thought it looked as though someone had smeared the distant horizon with blood from the obstetrics table. As if to escape from the bloodstain, he stepped on the accelerator. Almost at the same moment, a siren sounded, so loudly that it felt like the ground was shaking. He imagined the high-pitched siren puncturing the clear blue sky over his head, leaving it with hundreds of holes.

Instead of the bloody red, Feng Jian

now saw a white void. He realized that he had driven through a red light. “Damn it!”

A policeman got out of the patrol car and walked over. He was tall and sturdy, with [add a] receding hair line. He asked, smiling, whether Feng Jian knew the speed limit. Feng Jian murmured, “Sixty kilometres.” The policeman then asked what his speed was when he went through the red light. Feng Jian lowered his head and said in a small voice that he did not know.

“One hundred and ten kilometres, sir!” the policeman said, holding his hand out for Feng Jian driver’s licence.

“I am sorry, officer. I did not mean to. My wife just gave birth to a baby. I have not slept since yesterday. I took the red light for blood … no, blood for the sun … no, no, no, I thought the red light was the sun. I do have a very good driving record. Could you…?”

“Congratulations, your wife had a baby! Boy or girl?”

“A girl,” he answered without enthusiasm.

“You are so lucky!” the policeman responded, with what Feng Jian thought was exaggerated zeal. “I have three boys. My God, I envy you!”

You envy me? It is I who should envy you, Feng Jian thought to himself.

“Anyway, you’re a father now, and you should be a more responsible and careful driver.” His booklet in hand, the policeman started to write out the fine. The smooth movement he made was like that of a knife slicing back and forth, each and every slice cutting into Feng Jian’s heart.

“Because your wife just gave birth to a daughter, I will only fine you for failing to stop at a red light. I could give you another one for speeding.” He gave Feng Jian the ticket for $140 along with his driver’s licence. With a shrug, he walked back to the police car. “Have a nice day!”

Nice day? Are you joking? Getting another daughter and a fine on the same day, Feng Jian felt he was totally out of luck. He threw the ticket on the passenger seat and started the engine with a trembling hand. He had to get to his friends’ place fast. Jiajia, his oldest daughter, had been staying with the Tangs’ for two days. He must pick her up, get back home, make some chicken soup, and take it to his wife.

On his way home, Feng Jian began to brood. He couldn’t understand why he and his brothers were unable to produce a single male child. Because it had so many boys, the Feng family used to be the envy of the neighbourhood in his hometown. What was wrong with his generation? After he had his first daughter, his two younger brothers had daughters in quick succession, as if they were in a competition with him. The Chinese used to believe that the greatest offence against filial piety was failing to produce a grandson. Of course, Feng Jian1 was not so old fashioned that he would share such a feudalistic and patriarchal attitude. However, his dear mother did not get along with her sister-in-law. His uncle’s wife had two sons and a daughter, and they had two boys and a girl, too. She was extremely pleased with her good luck at having two grandsons, and her smug contentment offended Feng Jian’s mother, who felt that she could not hold her head high whenever she bumped into a neighbour with a grandson. His mother’s sighs could have filled up a large oxygen cylinder.

Feng Jian felt obliged to cure his mother’s unhappiness by giving her a grandson. So he began to consider emigrating to Canada.2 Fortunately he was in the right profession and had earned some good money a few years back when he had worked in Shenzhen. When he went on a seven-day tour of Hong Kong, he consulted an immigration agency there. The consultant estimated that he could score seventy-four points, so he paid six thousand U.S. Adollars there and then. He left Hong Kong and waited back home. Sixteen months later, he and his family arrived in Toronto.

Upon arrival, other new immigrants started English lessons and job hunting right away. Feng Jian, however, immediately went on an information-gathering mission to ensure that the next child he had would be a boy. Someone told him that changing their diet was essential because high protein and high sugar food, supposedly, boosted the chance of having a girl. Consequently, the Feng household stopped purchasing anything sweet, and even stopped adding sugar to pork stew, their favourite dish. Someone else suggested that his wife, Sheng Jiqi, use soda to cleanse her private parts before going to bed. This method was said to be scientifically sound and highly effective, because the Y chromosomes that produce a male child could only survive in a slightly alkaline environment. Since a daily soda rinse could produce such a condition, the probability of producing a boy was as high as ninety-two percent. It was nicknamed “the scientific way to cultivate the land.” So the bathroom in the Feng household now contained a box or two of baking soda.

Four months later, Sheng Jiqi calculated that her period was about ten days late. It so happened that their OHIP coverage had gone into effect as well, so she went to see a family doctor who confirmed that she was indeed pregnant. By then, they had been following the new diet for three months, and she had been rinsing with soda for about two months. She also felt different this time compared to her first pregnancy. Feng and Sheng were delighted. When Sheng Jiqi was seven months pregnant, their friends and their landlady told them that the shape of her belly indicated she was having a boy. According to them, if a pregnant woman had a dome-like belly and the tip of the dome leant forward, she was carrying a boy. If she was carrying a girl, her belly would be in a ball shape, bulging out front and back. Sheng Jiqi had a dome-shaped belly. The couple were overcome with joy.

When the doctor said “Congratulations” to him after the baby was born, Feng Jian assumed that it was a boy. “It’s a pretty girl!” the doctor continued. Feng was left dumbfounded.

Fortunately, they had not told their relatives back in China that Sheng had been pregnant because they had planned to give them a pleasant surprise. Instead, they had another daughter!

The baby girl was, nevertheless, still their flesh and blood. They’d better get her a birth certificate, the nurse reminded him, when he took the chicken soup to the hospital. Feng Jian had chosen a name for a boy. His Chinese name would be Dawei, his English name Davie, and his diminutive name Dada. The Chinese and English names sounded alike; moreover, the characters were good, their sounds good and their connotations good, too. The names were just like their daughter’s: Jiajia in Chinese and Jessica in English, a good match. But now their original choice was useless. What would they call this little girl?

Sheng Jiqi insisted on naming her daughter Liana and giving her the pet name Nana. When Sheng was a girl, she had read a Russian novel whose heroine was called Liana. The character had left such an endearing impression that she had wanted to name her oldest daughter Liana. However, her sisters were strongly against it. They told her there were so many Mannas, Annas, and Lenas around that Liana had lost its exotic nature and become common. Now they were in Canada, and it did not matter if Liana was “common.” Feng Jian neither fancied nor hated the name, so he deferred to his wife’s preference and put Liana on the form the nurse had asked them to fill out.

“Come on Nana, let Daddy hold you so that Mommy can have some chicken soup.” Feng Jian took the baby from her mother and sighed. “Nana, it would be terrific if you were a boy. Then you would not be called Nana, but Dada and Davie. Just like your sister; she is Jiajia and Jessica. Jiajia-Jessica and Dada-Davie are beautiful and resounding names. Now you end up with Nana-Liana. Nana … Eventually, we’ll have Jiajia, Nana, and Dada. Jiajia, Nana, Dada? Hey, Jiqi, what do you think about these names?”

“What?” Sheng Jiqi was taken by surprise.

“Jiajia, Nana, Dada, Jia-Na-Da, don’t they sound like Ca-na-da? Let’s have another child and it will be a boy. Let’s have Jia-Na-Da! Canada!” Feng Jian warmed increasingly towards the idea. He had been exhausted, but now he felt rejuvenated. At that moment, having a son seemed as easy as pie.

“Another child? Do you really believe that the sole purpose of my coming to a foreign country is to bear children for your family? Am I a breeding machine to you?” Sheng Jiqi3 was upset. “Look at you. You have been in C

anada more than a year, and you still do not have a permanent job, just part-time jobs or contract work. Your income is as meagre as a labourer’s, and we have to use our savings to pay bills. And you still want another child!”

“There is nothing to worry about. We’ll have bread and milk, and I’ll find a real job. Also, don’t forget that you have promised.”

“What promise…? Your brothers tricked me.” Sheng Jiqi gave him an angry look. But she did recall the farewell banquet Feng Jian’s parents and brothers had thrown them on the eve of their departure.

At that banquet, one of Feng Jian’s younger brothers was a bit drunk after a few rounds of toasting. Acting upon the moment, he said to Sheng Jiqi, “Dear sister-in-law, please drink up.”Then, imitating a character in the Beijing opera The Red Lantern, he held up his glass and said, “May the weight of the revolutionary mission now fall on your shoulders!” Sheng Jiqi felt the blood rush to her head and her face burn. She knew what the “revolutionary mission” meant, and she found herself in a very awkward situation. She could not accept, nor could she reject, the toast. Immediately Feng’s mother and sisters-in-laws called out, “Yes, yes, drink up, drink up!” Facing all those expectant eyes, Sheng Jiqi simply could not say no, and so after a brief moment’s hesitation, she tilted her head backwards and drank up. From that moment on, the toast became a promise to Feng Jian, but to her it was an unbearable weight, especially now after giving birth to Nana.

Feng Jian persisted. “You know, the revolution is yet to succeed, and you and I must keep trying. If we do not have a son, how can we have the courage to face our loved ones in China? As for our life here, we can manage. Even if we did not work, our savings could still support us for a year or two. Haven’t you heard the saying that Canada means ‘da-jia-na,’ ‘na-da-jia,’ and ‘da-na-jia’? That is, ‘everyone dishes out from the big communal pot.’ If you have more children, you are entitled to more benefits; if you have fewer, you are entitled to fewer, and if you have none, you are entitled to nothing. So why not have more? If we have another child, we are simply taking a bit more from the big pot! Look at those refugees from all over the world. They all seem to have a brood of kids, and are they poorer than we? No. They can eat and drink until their bellies are full, and they can have whatever fun they fancy. Remember what our Prime Minister Jean Chrétien once said about those people: they just take welfare money and drink beer at home. They felt offended and went out to protest. That is truly “na-da-jia”—everyone is entitled to take what he wants from the communal pot. Admirable!”

Toward the North

Toward the North